There’s no shortage of ballsack beauty treatments on the market today. From injecting botox into the scrotum, or Scrotox, to testicular enlargement procedures, guys worldwide are willing to shell out top dollar for manhood makeovers.

We’re similarly obsessed with “rejuvenation” — i.e., the idea that science can make us young, horny and fertile. Balls — and not just human balls — have been experimented with for centuries in an effort to produce rejuvenating “elixirs,” and to fix drooping, aging boners. In the 20th century in particular, the promise of rejuvenation meant restoring fertility, curing impotence and, in some cases, offering up bizarre concoctions to put an overall pep in your step — and, of course, your junk.

Before the 20th century, doctors believed that jerking off too often would worsen your health, leading to anti-masturbation crusaders peddling quack campaigns to preserve male virility. This was made worse by the fact that many people also thought men had a finite amount of semen. And because big, full balls were thought to be markers of youth, plenty of guys worried about their virility sought out new ways to tinker with their testicles.

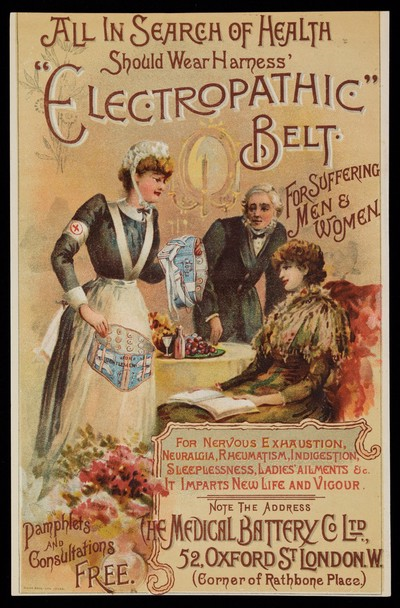

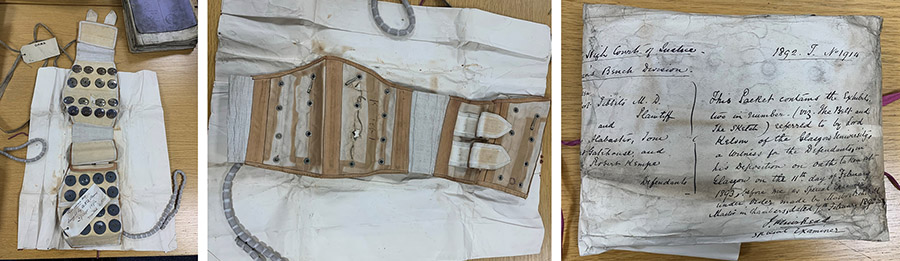

A 19th century ad promising to “restore your manhood” — or, in layman’s terms, to remedy your limp dick — could lead to you getting your balls shocked with electrical stimulators or whipped with a leather-tassel flogger, which might be the kinkiest “cure” for erectile dysfunction in recorded history. In the Victorian era — a time ripe with fear-mongering around jerking off and threats that it caused infertility and ill health — these medical quests to remedy impotence were the most sought-after types of “rejuvenation.”

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that testicular surgeries became a regular practice, thanks to guys like Dr. Serge Voronoff. As a young surgeon tasked with “improving” various farm animals, he started transplanting testicles from younger to older breeds of sheep, bulls and goats in the hopes of “restoring lost vigor.” He studied eunuchs while working in Cairo and roasted them in his reports, noting their “obesity, lack of body hair and broad pelvises, as well as their flaccid muscles [and] lethargic movements.” In his eyes, all their ailments came down to their lack of balls.

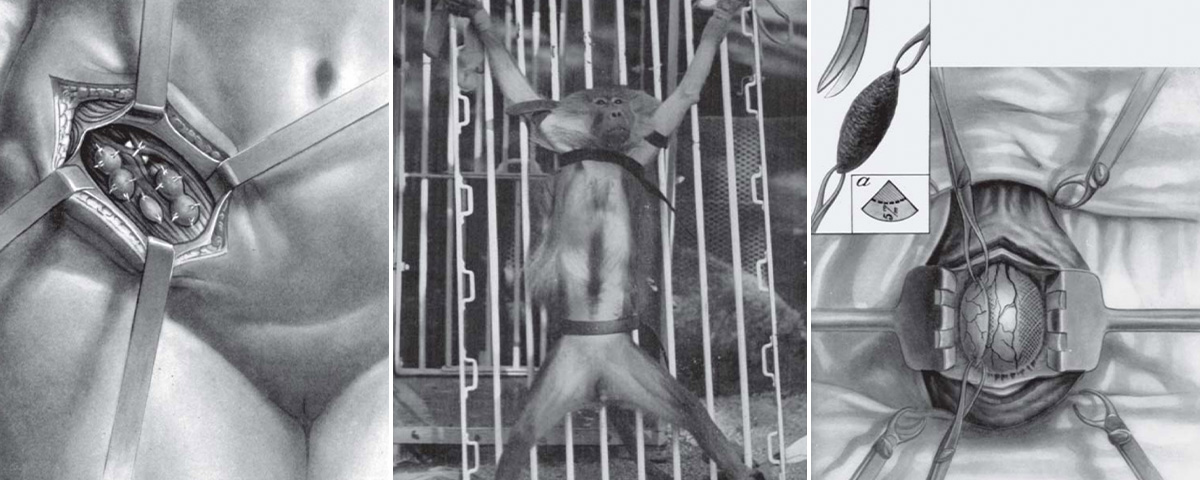

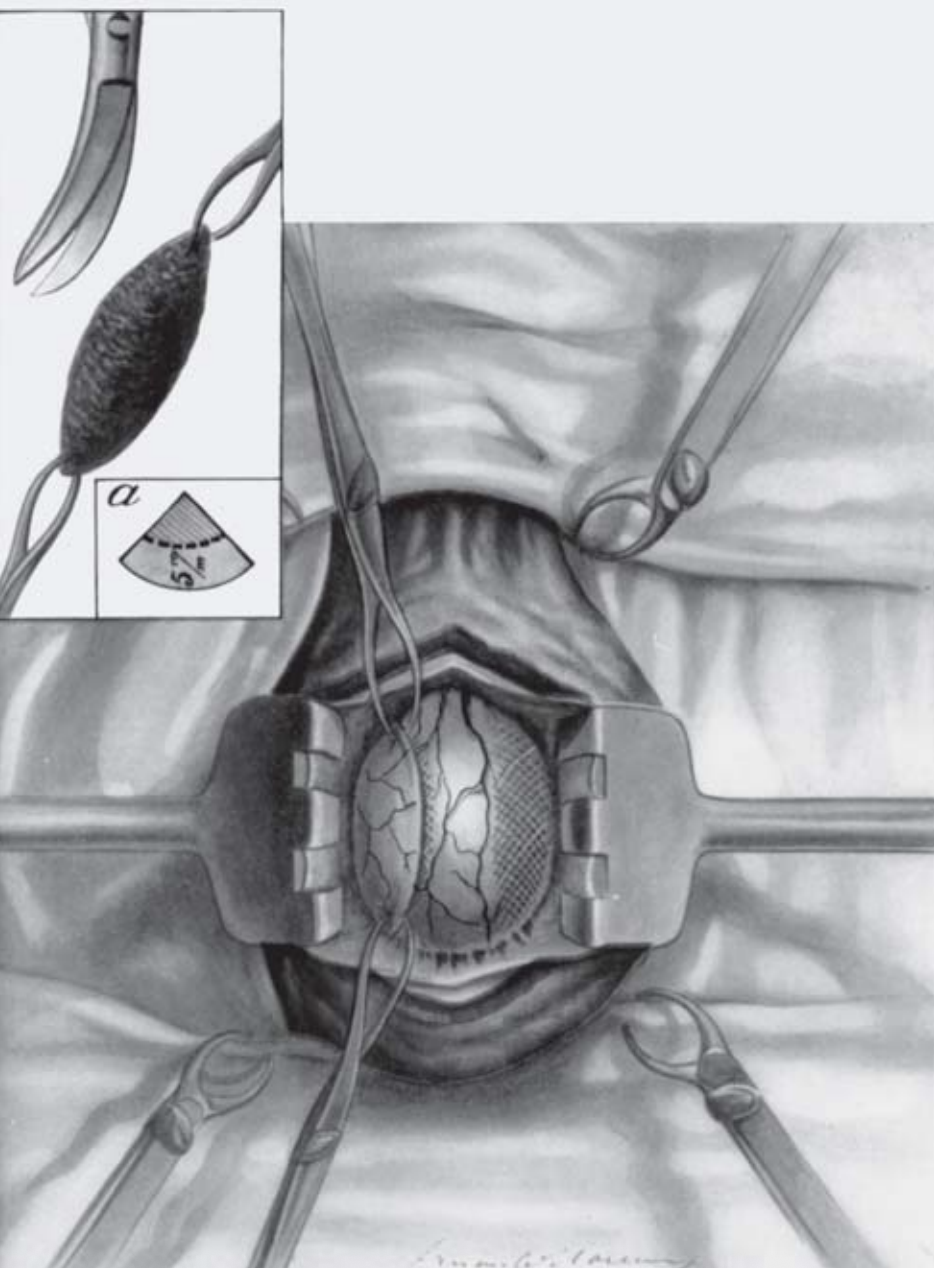

Voronoff moved to Paris and expanded his knowledge; by the 1920s, he had started grafting monkey nuts into human scrotums, a process he branded as a kind of rejuvenation procedure. Prior to this, testicular surgeries had been performed for strictly medical reasons, like treating undescended testes. Voronoff was one of the first to market a testicular transplant as some kind of youth-restoring miracle procedure.

Voronoff, who viewed testicles like miracle glands, promised this scrotal switch could “improve memory, reduce fatigue, enhance eyesight and libido” and even lengthen life. The ultra-wealthy traveled many miles for these monkey ball implants, so much so that Voronoff opened a monkey farm in an Italian villa — known as Voronoff’s Castle — complete with a lab to collect tissue.

This wasn’t the only testicle-related “rejuvenation” fad of the time either — although it was the first to require an actual ball transplant in order to work. In the late 1890s, Mauritian physiologist and neurologist Charles-Édouard Séquard-Brown had engrossed the world by injecting his “elixir of life,” actually a potent mix of secretions from the balls of poor dogs and guinea pigs. Séquard-Brown and his acolytes cemented the sacred status of testicles as anatomical deities; squishy, precious pearls of manly vigor.

The early 1920s also saw the rise of Austrian physiologist Eugen Steinach, who basically believed gay men suffered from faulty balls that produced feminizing hormones. He pioneered what was essentially testicular conversion therapy, transferring the ball of a seemingly straight guy into the scrotum of a gay guy. Unsurprisingly, these treatments were unsuccessful.

All things considered then, Scrotox doesn’t sound so bad after all.

0 Comments